In the wave of data about higher education that the White House released last weekend, one fact emerges that was already painfully clear: The “haves” in higher education have quite a lot; the "have-nots" struggle mightily.

President Obama had been talking for some time now about creating a Consumer Reports-style college ratings system. On Saturday, the president unveiled his much-anticipated College Scorecard.

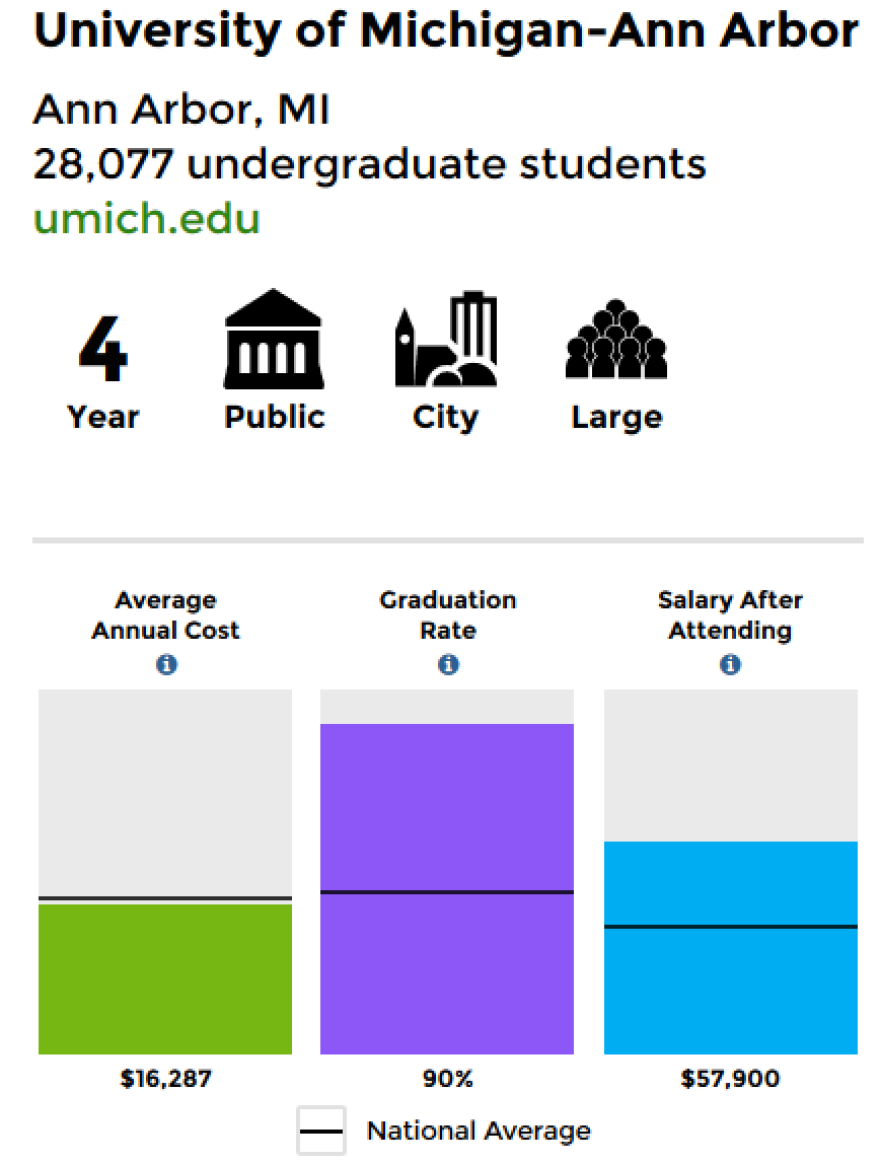

"You'll be able to see how much each school's graduates earn, how much debt they graduate with, and what percentage of a school's students can pay back their loans," the president said in his weekly address.

Colleges give prospective students very little information about how much money they can expect to earn in the job market. The scorecard is intended as a means to partially fill that information gap. To create the rankings the Department of Education matched data from the federal student financial aid system to federal tax returns. That data was then used to track how much money students who enrolled in individual colleges in 2001 and 2002 were earning 10 years later.

At first glance, the trends aren’t too surprising: students who went to wealthy, elite colleges earn more than those who do not. But the deeper you crawl into the data, the more clear it becomes how risky the higher education market can be for students making expensive, important choices that don’t always pay off.

According to analysis from ProPublica, some of the nation’s wealthiest colleges are leaving their poorest students with plenty of debt.

Take New York University, for example. NYU is among the country’s wealthiest schools with a $3.5 billion endowment, and campuses in Abu Dhabi and Shanghai, as well as billions invested in SoHo real estate.

However, as ProPublica reports:

“The university (NYU) does less than many other schools when it comes to one thing: helping its poor students. The school’s Pell Grant recipients – students from families that make less than $30,000 a year – owe an average of $23,250 in federal loans after graduation. That’s more federal loan debt than low-income students take on at for-profit giant University of Phoenix, though NYU graduates have higher earnings and default less on their debt."

But NYU isn’t the only university with a billion-dollar endowment to leave its poorest students with heavy debt loads. More than a quarter of the nation’s 60 wealthiest universities leave their low-income students owing an average of more than $20,000 in federal loans.

At the University of Southern California, which has a $4.6 billion endowment, low-income students graduate with slightly more debt than NYU’s graduates: $23,375. At the University of Michigan ($9.7 billion endowment) it's $21,270, and at Michigan State ($2.5 billion endowment) it's $25,500.

As ProPublica points out, the implications of these numbers are quite significant. “Studies have shown that even small debts can increase a student’s chances of dropping out, particularly for minorities and low-income students. Also, federal loans, which are typically capped at $27,000 over four years, often don’t cover the full expense of college.”

We also know this economic gap is seriously influenced by gender, race and social class – issues on which the College Scorecard is silent, but which affect just about every data point presented.

Some have taken issue with this kind of “value-neutral” approach the White House has taken when reporting earnings data. Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, writes in Huffington Post that earnings data does not account for differences in mission of institutions, some of which have different values from wealthier universities, all while ignoring the pernicious effects of gender and race discrimination on career opportunities and earnings.

“The colleges and universities with the highest earners have pitiful proportions of black students and Pell recipients, and modest enrollment of women. A synopsis of the data shows that the private nonprofits (which include the wealthiest universities in the nation) earn on average $81,900; for that group of schools, the proportion of black students enrolled is just 5%, women are 40%, with Pell Grantees just 16%,” McGuire notes.

McGuire maintains the the College Scorecard also ignores the increasingly non-traditional nature of the nation's undergraduate student body, and obscures some of the most important questions in the college choice process: What are the student's abilities? Where will she get the best academic advising and support services? Where will he have the best access to faculty? And what is the campus climate for women, or students with disabilities or children?

It is also worth considering that defining college outcomes in purely economic outcomes risks exacerbating what Frederik deBoer calls the "corporatization of the modern university." Students do get a lot more out of college than just earnings potential. They learn to be better citizens and better human beings. The world needs teachers and artists along with the future tech entrepreneurs and attorneys.