Neighborhoods matter.

A big part of the reason why is that good neighborhoods usually have better schools.

But across the country, the number of kids actually attending their neighborhood schools is declining. The most recent data show around 13% of public school students attend a school other than the one they were assigned. MLive found that in Michigan, that number is significantly higher – with 23% of Michigan students leaving their assigned public school for a charter school or another district.

This fact is especially visible in Detroit, where many students commute long distances to attend schools run by over a dozen different districts and charter school authorizers.

School choice advocates say this has given Detroit children a chance to escape chronically low-performing neighborhood schools. But others say it’s created a landscape with little accountability or coordination between different educational entities.

So, how did Michigan’s largest school district become what some describe as the “wild west” of education? Let’s take a look.

Researchers at LOVELAND Technologies spent a year and a half researching the history of Michigan’s largest school district. What they found is that Michigan’s largest school district has always struggled to keep pace with a rapidly changing city.

The early days

Around five years after Michigan became a state, the Detroit Board of Education was created to oversee publicly funded schools in the city. Their number one problem at the time? Space. As the city’s population grew during the 1800s, makeshift classrooms popped up in storefronts and church basements across the city. By 1900, the Board of Education had built nearly 90 new schools to accommodate the growing city.

Then came the car

The invention of the car in the late 19th century rapidly transformed Detroit, and the city soon became synonymous with American auto manufacturing. Workers from across the world flocked to the Motor City’s assembly lines. Between 1900 and 1930, Detroit’s population grew by more than 400%. And that growth looked very different in Detroit than it had in other cities.

From the report:

Unlike older cities like Chicago and New York, Detroit’s growth period came at a time when car ownership was more affordable, and as a result workers could live further away from the factories and commute to work. Instead of growing upward with high-rise apartment buildings, the city grew outward, with rows of single-family homes stretching for miles outside of downtown.

As Detroit’s population moved out into surrounding neighborhoods, the city focused on building neighborhood schools that were within walking distance for students. By the time it reached peak enrollment in 1966 with nearly 300,000 students, the district had more than 370 buildings spread out across the city.

By the time it reached peak enrollment in 1966 with nearly 300,000 students, the district had more than 370 buildings spread out across the city.

From boom to bust

Starting in the 1950s, the automobile plants that had drawn hundreds of thousands of workers to Detroit started moving to the suburbs. Jobs and tax revenue went with them and the school district started shrinking. The city's growing African-American population also led to increasing tensions between black and white residents, especially when it came to schools.

As the report notes:

The Civil Rights movement marked the beginning of the end of Detroit’s de facto school segregation, and court-mandated “bussing” programs that brought black students to what had been mostly white schools led many parents to withdraw their children from the public schools, accelerating the decline in enrollment. This began a downward spiral of enrollment, reduced funding, and disinvestment in schools, which led to further enrollment loss.

The district now had too many schools and not enough students. So, starting in the 1970s, it began to close buildings. The district closed 14 schools in 1976, 15 schools in 1986, and then another nine in 1990. At the same time, numerous teacher strikes and administrative corruption undermined families’ confidence in Detroit Public Schools.

Reforms reshape educational landscape

Calls for reform spurred by the deteriorating situation in Detroit Public Schools led to legislative changes that would have a lasting impact on the district. In the mid to late 1990s, Michigan state legislators passed laws that would allow for the creation of charter schools as well as give families the option to attend other school districts.

Families in Detroit flocked to the new options, and by the end of the decade, the district was again facing steep declines in enrollment. With each student that left for a charter school or a suburban district, Detroit Public Schools lost over $6,000 in state funding. The result was a multi-million dollar budget crisis.

At the same time, the district was actually in the midst of major renovations and the first new construction in 20 years.

According to the report:

Between 1999 and 2012, over $78 million dollars was spent upgrading schools that later closed. Another $27 million dollars was invested in schools that were closed and demolished a few years later. Sherrard Elementary was renovated in 2002 at a cost of $1.4 million dollars, only to close in 2007. By 2005 $3.9 million had been spent on new athletic fields at Redford High School, which closed just two years later.

The school closures pushed many frustrated parents to leave the district for what they hoped would be greener pastures. By 2013, there were more students enrolled in public charters than in DPS. And today, more than 60,000 students living in the city use school of choice to attend charter schools or suburban districts.

Today, more than 60,000 students living in the city use school of choice to attend charter schools or suburban districts.

The state steps in

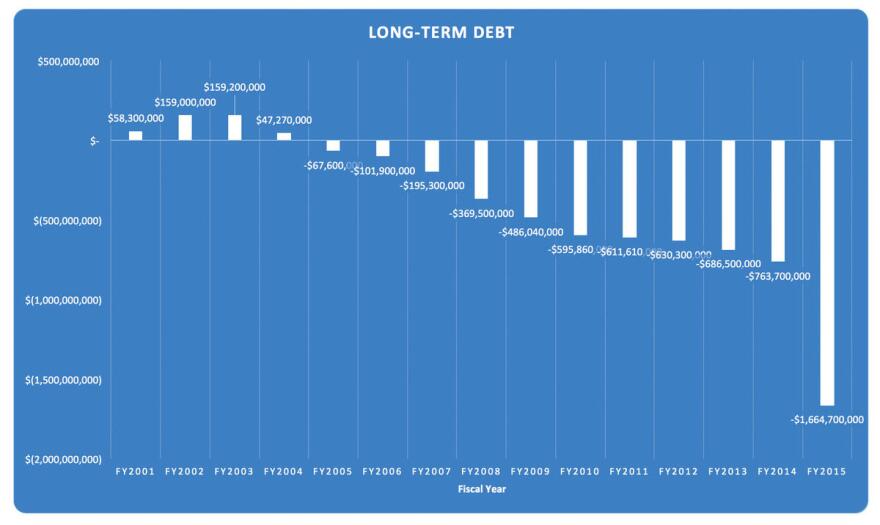

In response to the increasingly precarious finances of DPS, the State of Michigan appointed an emergency manager to the district in 1999 – although it's notable that the school system was actually running a budget surplus then. Control of the district returned to an elected school board in 2005, but the state again took over in 2009. DPS has had a string of emergency managers since then, but none managed to reign in the hundreds of millions of dollars of debt or stem the loss of students.

The district continued to close schools to try to deal with the massive financial losses. Since 2000, 195 Detroit schools have closed their doors. But the savings that were supposed to come along with that were undermined by poor planning and the costs of securing empty buildings. And each school closing, the report says, only pushed more families to seek other options for their kids.

As Detroit Public Schools neared the end of the 2015-16 school year, the district was $467 million in debt and on the verge of bankruptcy. After months of negotiation in Lansing, state lawmakers in June passed a legislative package that would help DPS avoid a shutdown. The package splits the school district into two parts. The old Detroit Public Schools exists solely to pay off debt with local tax dollars. The new district – now known as Detroit Public Schools Community District – will be in the business of actually educating students.

A fresh start?

Students will start this school year in a new debt-free district. But critics of the deal say it functions more as a band-aid than a long-term solution. One of the major sticking points during negotiations over the legislation was the creation of a Detroit Education Commission, which would oversee the opening and closing of schools in the city. The original Senate version of the legislation included that provision, but it was missing from the final bailout package signed by Governor Rick Snyder.

Still, district officials are trying to reassure parents and teachers that the transition to the new district will be a smooth one. And while enrollment is expected to decline slightly, the district is making an effort to attract families with new offerings like Montessori programs in seven of its elementary schools. Whether those efforts will be enough to reverse the decline that has been decades in the making remains to be seen.