It was February 2006, almost exactly 10 years ago, when then-governor Jennifer Granholm used her weekly radio address to urge state lawmakers to pass a new set of rigorous high school curriculum requirements.

"We have to increase the skill level of our students," Granholm said. "We have to increase our efforts to give our children, who are our future workforce, the math and science education they need to succeed in the 21st century."

The Legislature acted, and the next school year, the Michigan Merit Curriculum went into effect.

Now, nearly 10 years later, we may finally have an answer on whether it worked.

The Michigan Merit Curriculum made it a requirement for Michigan’s high school students to take at least four years of math, at least up through Algebra II, and for them to take at least three years of science, among other requirements.

It was about raising the skills of Michigan’s kids to meet the demands of employers. But it was also about raising expectations, to fight what George W. Bush had famously called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Last week, researchers at the University of Michigan and Michigan State published a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research on what the curriculum changes actually accomplished.

(You can read a policy brief on that paper here.)

"As the title of our paper suggests, the higher expectations alone were not sufficient to really improve student outcomes," says Brian Jacob, a U of M professor and the lead author of the paper.

The paper looked at ACT scores for individual students, and whether those students graduated.

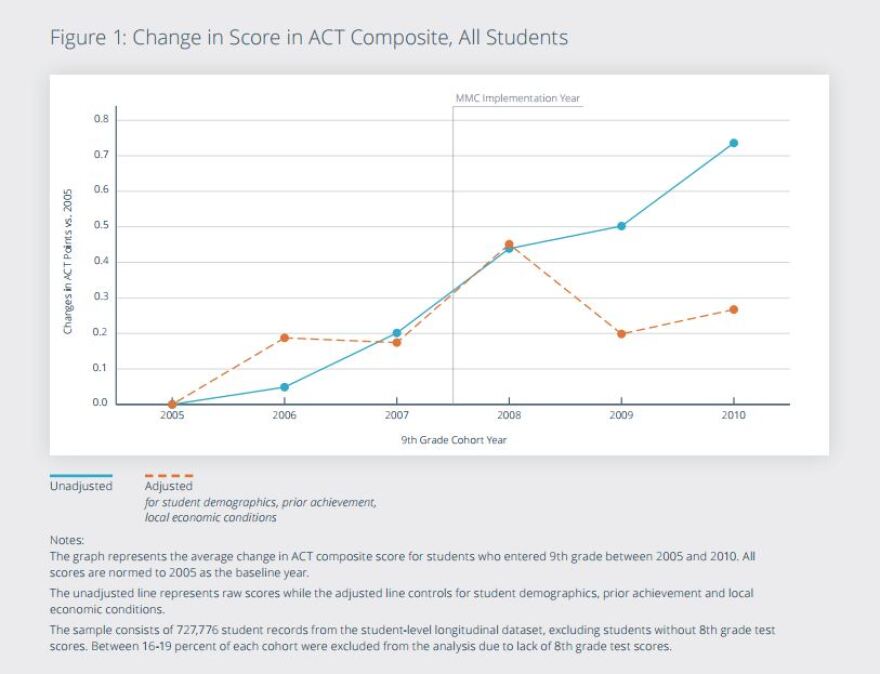

And, basically, Jacob and his coauthors found the new curriculum had no major effect on those things. It’s true that student scores and graduation rates had been improving before the curriculum went into place. That trend continued.

"So it looked like students had been improving a little bit before the new curriculum requirements, and they continued to improve roughly at the same rate after the curriculum requirements," Jacob says. "So, while that’s in general good news for students themselves, that suggests the new requirements themselves weren’t having much of an impact."

... the basic message is kind of a boring one: it wasn't a huge success, and it wasn't a huge failure. Things just basically stayed on the same track as before.

There were a lot of other calculations that went into drawing that conclusion. And there were some small effects - a small improvement in science scores for some students, a small decline in graduation rates for some students. But Jacob says the basic message is kind of a boring one: it wasn’t a huge success, and it wasn’t a huge failure. Things just basically stayed on the same track as before.

What will the state do with that information?

"I think these results underscore the importance of high expectations for students, but also that having the expectations is not enough," says Venessa Keesler, deputy superintendent at the Michigan Department of Education.

She’s seen the study because the MDE was involved in the study. And that alone, she says was important – that the department itself is trying to get good information on whether its policies are working.

But also Keesler says, it shows that policymakers need to take a more comprehensive look at what’s needed to improve results.

"I think this study helps us understand the importance of having multiple strategies to help increase achievement for students," Keesler says, "and understand that any one strategy alone may not be enough for certain student populations."

So now, Keesler says, the Department of Education is pursuing a new goal to make Michigan a top 10 education state. But that goal isn’t just about pushing more rigorous classes. It’s about finding services for kids who need it. It’s about looking at things like discipline and behavior and factors outside of school.

It could take a long time to find out if this approach is any better.

Maybe, 10 years from now, there will be a new study.