Closing the achievement gapbetween kids from different economic backgrounds is one of the most important challenges facing the U.S. education system today. It is also an expensive undertaking. With all the preschool programs, tutoring programs, afterschool programs and social service programs directed at helping kids from low-income families, the United States easily spends billions every year on this problem.

Which is why anew research paperpublished today by the National Bureau of Economic Research holds such promise. The paper analyzes results from a randomized experiment of a reading program put in place in 463 North Carolina classrooms. The results were striking: At a cost of just $250 - $400 per student, the program raised reading scores for third graders enough to take a significant chunk out of the achievement gap. Other programs with similar results can costs thousands per student.

The program is called Project READS. And though its results seem hugely promising, there is one catch.

The positive effects of the program only applied to girls. Boys who participated didn't see much improvement.

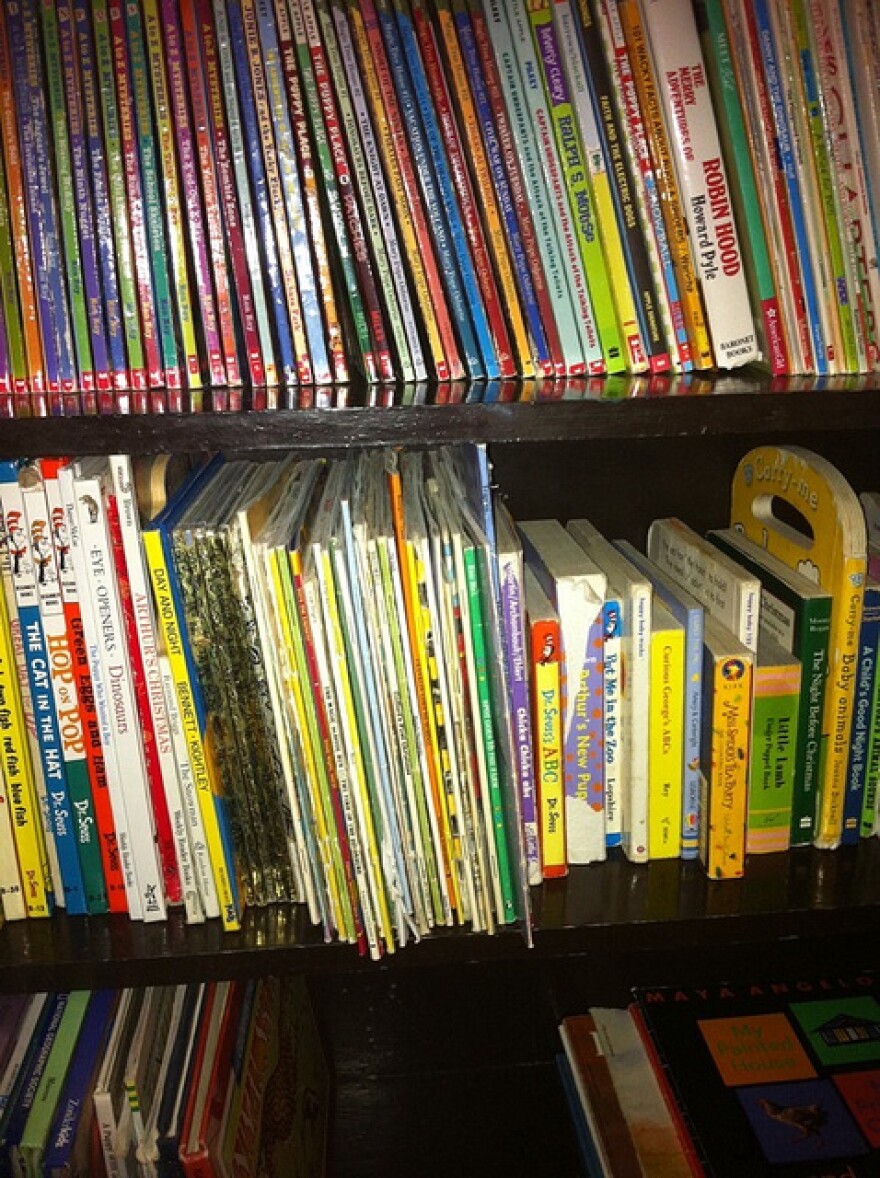

The idea behind Project READS is pretty straightforward. READS is an acronym that stands for "Reading Enhances Achievement During Summer." Kids in the program were sent free books in the mail while school was out for the summer. They were given guidance and encouragement to read the books, but they weren't forced to do so. The study also included a control group. In that group, kids didn't get any free books, though they could read on their own.

Turns out, kids who got free books in the mail did read more, on average, than the other kids. It may have helped that the books sent home were individually matched to each student's interest and reading level. Students were also asked to fill out and return a brief questionnaire to see if they'd understood the book.

When school resumed in the fall, both groups – the kids who got free summer books, and those who didn't – were tested on their reading comprehension.

This is a remarkably potent result for an investment of no more than $400 per student. Every year, school districts spend way more on programs that achieve way less.

The students who showed the biggest improvements were girls who started the program as third graders. The gain in reading scores was roughly equivalent to 1.4 months worth of learning. Or, looked at another way, it was enough to erase about 9 percent of the average reading score gap between kids from low-income families and kids from high-income families.

This is a remarkably potent result for an investment of no more than $400 per student. Every year, school districts spend way more on programs that achieve way less.

The problem is that, at least according to the results published in this paper, Project READS was totally ineffective at helping boys. Third-grade boys who got the free books over the summer showed no significant reading score gains compared to those who were just left to their own devices. The researchers had no clear answer on why this was the case. All they could offer is speculation:

It may be that reading during the summer builds reading skills for girls but not for boys. It is also possible that on average when 3rd grade girls read during the summer, they do so in a productive way whereas 3rd grade boys tend not to. This would be consistent with research showing that girls tend to have more positive attitudes toward recreational reading than boys (Logan and Johnston 2009) and that parents are more likely to read to girls than boys when they are younger (Bertrand and Pan 2013). For boys, but not for girls, there was some weak evidence that the amount they liked the books they read during the summer may have contributed to improved reading skills. It may be the case that when boys find books that they like, they read in a more engaged and focused way and build reading skills as a result.

Perhaps Project READS simply failed at knowing which kinds of books boys would like to read. The study doesn't really prove the case either way.

But the results for girls are significant enough that it seems worth figuring out how to get the same result for boys. It's not often that education researchers come across an idea for erasing achievement gaps that's both cheap and easy to implement. If it can be proven to work for boys as well as girls, maybe all school districts will start sending home free books during the summer.